A Movie Without A Hero

I've no idea if 19th-century English novelist William Makepeace Thackeray in any way inspired Martin Scorsese's Casino (screenplay by Nicholas Pileggi and Martin Scorsese from Pileggi's non-fiction book Casino: Love and Honor in Las Vegas). But I can't imagine the notoriously cynical author of The Luck of Barry Lyndon (1844) and Vanity Fair (1887) would take issue with my updating the latter's subtitle to headline this essay on Martin Scorsese's mythic epic of misanthropy, Casino; an operatically grandiose fall-from-grace fable lacking in even a single virtuous character.

|

| Robert De Niro as Sam "Ace" Rothstein |

|

| Sharon Stone as Ginger McKenna |

.JPG) |

| Joe Pesci as Nicky Santoro |

.jpg) |

| James Woods as Lester Diamond |

|

| Alan King as Andy Stone |

.png) |

| Don Rickles as Billy Sherbert |

Based on a true story and shot in a lacquered, color-saturated style befitting the over-the-top, tacky opulence of its '70s-era Las Vegas setting, Martin Scorsese's Casino is mobster neo-noir (neon-noir?) on an operatic scale.

A sprawling, blood-soaked, true-crime chronicle of the days of Mafia-ruled Las Vegas, Casino dramatizes a period in history when Sin City was still a slightly shady, post-Rat Pack, strictly-adults playground (no kid-friendly thrill rides), and the casinos served as the perfect false fronts of legitimacy for the Syndicate's meticulously planned and carried out money-skimming operations.

As Mob films go, Casino doesn't cover much new ground (especially if you've seen Goodfellas), but as the saying goes, it's not the tale; it's in the telling.

And from Casino's nearly three-hour running time, ten-year narrative span (1973 to 1983), prodigious body count tally (upwards of 24), and cast of over 100 speaking parts, all sporting more eye-popping retro costumes and hairstyles than a Cher retrospective; the telling is a clear case of form meeting function. Casino is the gangster movie recontextualized as a Paradise Lost parable advocating that you can take the wiseguy out of the mean streets, but you can't take the hood out of the hoodlum.

The paradox of Las Vegas has always been that it's a city built on games of chance

that stays profitable by making sure absolutely nothing is left to chance.

Casino kicks off with a (literally) explosive pre-credits sequence that hurls the audience and the just-seconds-old movie into "whodunit" territory with an abruptness of violence we'll come to learn is something of a Casino leitmotif. As an exercise in cinema economy, it's a killer of an opening (heh -heh) that instantly creates tension, disrupts the viewer's equilibrium (you're on guard against the unexpected before you've even had time to develop expectations), and establishes the basis for Casino's told-in-flashback structure and running voiceover narration.

.png) |

| Duel in the Sun |

Said voiceover duties are shared (in often amusingly contradictory and self-serving narrative perspectives) by childhood pals Sam "Ace" Rothstein (sports handicapper) and Nicky Santoro (protection racket). A pair of Midwest Mafia golden boys granted (temporarily, as it turns out) the Keys to the Kingdom, and for Ace, an ill-omened stab at absolution through love (enter, traffic-stopping Vegas hustler Ginger McKenna).

For all that I love about Casino—and I am indeed crazy about this flick...exhilarating and ambitious, it's precisely the kind of movie that reminds me why I fell in love with movies in the first place—the main reason it ranks #1 as both my favorite and most re-watched of Scorsese films, is the toxic trio of characters at its center.

|

| An Ace, A Queen, and A Joker |

"It should'a been perfect. I mean, he had me, Nicky Santoro, his best friend, watching his ass.

And he had Ginger, the woman he loved, on his arm, But in the end, we fucked it all up."

Anyone familiar with this blog is aware that I have a fondness for - as I once described it: "Movies about neurotic characters in mutually dependent relationships, each harboring barely-suppressed hostilities and resentments, yet forced by circumstance to interact" (e.g., Carnage, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Closer, A Delicate Balance).

So it should come as no surprise that I find the positively electric De Niro-Stone-Pesci/Ace-Ginger-Nicky dynamic of dysfunction the most compelling thing about Casino. No matter how big the film gets, the human scale always towers far above it. Scorsese, the master of the intimate epic, keeps the emotional drama center stage, while the actors somehow pull off the miraculous feat of humanizing these reprehensible characters without glorifying them.

|

| ROGUES GALLERY Clockwise from left: Frank Vincent, Kevin Pollak, Dick Smothers, and L.Q. Jones |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS MOVIE

In addition to being fascinated by films about corrosive relationships, I also have a mania for movies about ostensibly "foolproof" schemes that go calamitously wrong (e.g., The Killing -1956, A Simple Plan - 1998, and Before the Devil Knows You're Dead - 2007). Perhaps it's because I've always been somewhat allergic to the self-aggrandizing side of the "hero myth" in American movies (one of the main reasons I've never cared for Westerns, war movies, or sports films); or maybe because real-life keeps offering daily confirmation that America's staunchest and most noble institutions are no match for America's simpletons.

Whatever the reason (and it could be as simple as me relishing the tenets of film noir), I remain captivated by films that dramatize this almost biblical sociopsychological truth: There is no paradise so abundant, answered prayer so fulfilling, utopia so ideal, or technological advancement so life-changing that humans can't ultimately find a way to fuck it up.

.png) |

| Las Vegas as American Metaphor Devoted to upholding the illusion of fairness while knowing absolutely everything is rigged |

Although I liked Scorsese's Goodfellas (1990) a great deal, I'm one of the few (only?) who finds Casino to be the superior film. In melding two of my favorite movie subgenres (dysfunctional relationships/things spiraling out of control), Casino plays less like a gangster film to me and more like a conflict of human nature melodrama. And that's a win.

What's most dramatically compelling to me is how the characters in Casino are handed a Syndicate Shangri-La, yet they can’t get out of the way of their own egos, jealousies, and weaknesses long enough to make it work. In this, Casino has always felt a bit to me like the coin flip-side to Bob Rafelson's The King of Marvin Gardens (1972)…both films share a very late-‘70s, nihilistic sensibility in their attitude towards dreams, dreamers who fly too close to the sun, and the perils of mere mortals thinking they can play fast and loose with The Fates.

|

| "Beautiful title sequence of our lead character falling slowly into hell." Editor Thelma Schoonmaker on Casino's titles designed by Elaine & Saul Bass |

Religion almost always serves a function in Scorsese's films. Casino's themes reference Christian mythology. Specifically the notion of sin and absolution.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

Scorsese is such a gifted visual storyteller. Early in Casino, we're treated to an aerial nighttime view of Las Vegas—an isolated, neon-lit island in a vast sea of darkness—that succinctly captures the precise appeal this desert metropolis holds for Midwest mobsters: no neighbors.

Set smack in the middle of nowhere, Las Vegas is presented as a place apart. A world unto itself. An uncharted frontier where laws (and hands) can be broken, and ordinary rules of behavior simply don't come into play. No wonder Ace Rothstein calls it a gangster's "Paradise on earth."

While voiceover narration informs us that Vegas was wide open for guys like Ace and Nicky, Casino's visuals tell another story. The world of gambling casinos is a darkness-shrouded time/space limbo devoid of clocks or windows, illuminated exclusively by ceilings of neon suns and electric stars. Scorsese's frequent use of low-angle shots makes these ceilings look oppressive and looming, the casinos, closed-in and claustrophobic. Ace and Nicky like to think of themselves as free agents, but with cameras everywhere and the Mob bosses regularly reported-to, they're just two wealth-cocooned street guys living in garish gilded cages.

.png) |

| With Plenty of Money and You |

Scorsese's Las Vegas -an entire city done in exclamation points- is so isolated that it's not just out of touch with the rest of the world; it's out of touch with reality.

Everything from the cinematography (Casino has the sheen and saturated colors of a movie musical), period costuming (the '70s on steroids), and production design (gaudy glitz) to the editing (kid-in-a-candy-store jittery) reinforce a vision of Las Vegas as an oasis of overstatement.

|

| Sexy Beast |

PERFORMANCES

It's no surprise that De Niro and Pesci are phenomenal. They exhibit the same natural, improvisational intensity and chemistry they shared in Raging Bull and Goodfellas. (Although I confess that getting used to Pesci's voiceover initially took me a while. Nowadays, I delight in Pesci's profanity-laced commentary, but the first time I saw Casino, it felt as though I were trapped listening to an entire film narrated by Fats, that creepy ventriloquist doll in Magic - 1978).

But Sharon Stone is the real revelation in Casino. Giving the film's only Oscar-nominated performance, Stone brings it and is not fucking around. She owns that role and slays in every scene. I'll go to my grave saying she was robbed of the Oscar that year (she lost it to Susan Sarandon in Dead Man Walking).

Stone gives a career-best performance and damn-near steals the entire movie, inhabiting her character with both a granite toughness and raw vulnerability...her skill in conveying the latter is the very thing that makes the Ace/Ginger scenes work: if we didn't get a glimpse of the "other" Ginger that Ace falls in love with, he would simply come across as a fool. Sharon Stone has so many great moments, but one of my favorites is a scene in a hotel room with Pesci, where he's warning her to be careful around Ace. Her delivery of the line: "I know. You don't have to tell me that. What do you think, I'm stupid?" and the look she gives him as he leaves (She's SO not stupid) just lays me out. Stone is hands-down 75% of why Casino ranks so high on my favorites chart.

|

| The Happy Couple |

When I said that Casino is a story lacking in a single virtuous character, that went double for the city of Las Vegas. The film treats Las Vegas as another character in this drama. A character as bereft of a moral core as any of its flesh-and-blood castmates.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

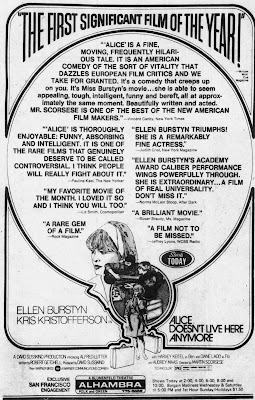

My favorite directors aren't favorites because I like all of their movies. I've seen nearly every film made by Martin Scorsese; some are dreadful (New York Stories – 1989), some are admirably flawed (New York, New York – 1977), some are unforgettable (Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore – 1974), and some are even masterpieces (Taxi Driver – 1976).

What tends to make a filmmaker a favorite is that their love of cinema is so passionate that even their failures are fascinating.

With Scorsese, I always get the feeling that he respects the power of film and enjoys manipulating the tools of the medium (music, editing, camera angles, production design, costuming, casting, dialogue, story) to create authentic cinema experiences.

Which means he leaves me to discover what I feel about what I see. He trusts me to do the work to interpret the unorthodox and risky. He understands that movies are about that magical exchange between the emotion of the story, the impact of the screen images, and the relationship forged with the viewer. Scorsese is a storyteller, and the obvious delight he takes in crafting a tale and bringing me into his world is as infectious as it is intoxicating.

So, on that score, Martin Scorsese is not one of those directors I can always count on to deliver a movie that I'm sure to love, but he's a director I definitely trust to deliver a movie that's about something human and real.

Though not very well-received when released, Casino, nevertheless, more than any other film he's made, embodies what I most love about movies and represents what I've come to most respect and admire in Martin Scorsese as an artist and a filmmaker.

|

| CASINO opened in Los Angeles on Wednesday, November 22, 1995 I saw it that following Saturday at Mann's Plaza Theater in Westwood |

.JPG)

.JPG)

.png)