For the unversed (or those who've

left the seventies back in the '70s where they belong), Rod Serling's Night Gallery is a suspense anthology TV series that ran

Wednesday evenings (final season: Sundays) on NBC from 1969 to 1973. A supernatural/horror follow-up to Serling's more sci-fi driven The Twilight Zone (1959 -1964)—still in heavy rerun rotation at

the time. Night Gallery most

definitely had its moments, but I remember it mainly as an exercise in protracted

fizzle.

As a means of building suspense in episodes whose narrative trajectories were telegraphed within minutes of their setup, it was common for even the

briefest of segments to be drawn out to almost comic effect. Episodes routinely featured

characters speaking in needlessly vague, cryptic language (

"You don't mean…!") that never came to the point. All while assiduously avoiding

any and all action that might bring about a resolution to their problem. Unfortunately, when it came time for the payoff, it always seemed as though the slower the buildup, the more unsatisfying and frustratingly ambiguous the final twist.

But as one does with SNL these

days—suffer through 95% of ho-hum in hopes of the occasional 5% of brilliant—Night Gallery was my Wednesday night

ritual. A ritual fueled in part by a pre-cable paucity of bedtime-stalling TV options, and that

still-mysterious-to-me adolescent fascination with horror and the desire to be frightened. Besides, whether good or bad, each Night

Gallery episode was sure to be the water fountain topic of conversation at

school on Thursday mornings, so one needed to be up on such things.

|

| Rod Serling on the cover of TV Guide - July 3, 1972 |

That

being said, it's still probable for the entire Night Gallery series to have remained just another dimly-remembered blip on my post-pubertal pop-culture

chart had it not been for the four profoundly memorable appearances made by

London-born actress Joanna Pettet during the program's three-season run. Holding what I believe to be the record for Night Gallery appearances, Pettet starred in four

mesmerizingly eerie segments which, due to their spectral eroticism and Pettet's mythic dream-girl persona, thoroughly captured my imagination and burned an

indelible tattoo on my teenage psyche. Even now, some 40+ years later, I still find these episodes to be as

hypnotically compelling and intoxicatingly seductive as ever.

|

| As Mata Bond in the James Bond spy spoof Casino Royale |

My initial familiarity with the work of Joanna

Pettet stemmed from the TV broadcast of

The Group (1966, her film

debut) and falling in love with her (and her killer dimpled smile) as Mata Bond in the overstuffed spoof

Casino Royale (1967). Both films are ensemble-cast efforts in which Pettet, by turns, distinguished herself splendidly as a talented

dramatic actress and as an appealing light comedienne. But by the time she made her first

Night Gallery appearance in 1970, the accessible, dimpled

ingénue had been replaced by the slinky, strikingly beautiful, irrefutably dangerous '70s equivalent

of the classic film noir Woman of Mystery.

As detailed in the marvelous

book Rod Serling's Night

Gallery: An After-Hours Tour by Scott Skelton and Jim Benson, Pettet consciously

used her Night Gallery appearances to cultivate a mysterious, ethereal screen

persona for herself. Adopting

a contemporary "look" every bit as smoldering and distinctive in the '70s as Lauren Bacall's was in the '40s, Pettet offset the aloof quality of her rail-thin physique, long hair, and angular

features with soft, gauzy "boho gypsy," "hippie chic" outfits from her own wardrobe. The combined effect was that of a modern seductress/enchantress: welcoming but unapproachable, a preternatural being who was very much of flesh and blood, yet something slightly less than real.

The dramatic landscape of early '70s television was largely male-centric, with women primarily occupying wife and girlfriend roles (

Wonder Woman,

The Bionic

Woman, and

Charlie's Angels would come along later). One of the reasons Pettet's

Night Gallery episodes stood out so firmly in my mind is that she broke the mold. This was no girl; this was a woman. She wasn't pliable, she wasn't agreeable, she wasn't even attainable. She was a distinct feminine force operating from a place of her own needs and desires. Provocative in her mysteriousness, the men in these narratives were drawn into HER orbit, not the other way around. The characters she played were enigmas – entities perhaps, more than real women – but they exuded elegance, romance, sex, and danger. All contributing to Joanna Pettet being the perfect neo-noir femme fatale for an age that held precious little in the way of sexual mystery.

The House - 1st Season: Air date December 30, 1970

Everything

Joanna Pettet would build upon to greater effect in future episodes of

Night Gallery appears for the first time

in "The House," a legitimately haunting ghost story that pivots 100% on Pettet's

wispy, wraithlike persona. In "The House," directed by John Astin (Gomez of

TV's

The Addam's Family) and adapted by

Rod Serling from a (very) short story by Andre Maurois, Pettet plays Elaine

Latimer, a somewhat chimerical former sanitarium patient –

"She's dreamy…Never walked. Just sort of wafted along like a wood

sprite. Never put her two feet on the ground." – plagued by a recurring

dream. Not a nightmare, but a tranquil, languorous dream in which she sees

herself driving up to a secluded country house, knocking on its door, but always

leaving just before the inhabitant answers.

The dream, a sun-dappled, slow-mo symphony of flowing hair and gossamer garments

billowing in the wind, replays over and over in this episode, creating a truly hypnotic effect once the events of the story (she finds the dream house in real life, only to discover it is haunted...but by whom?) call into question the very nature of reality and illusion.

When

a dream comes true, is it then a premonition? And when fantasy and reality merge,

can one honestly know where one ends and the other begins?

|

| Chasing Ghosts |

Whenever

anyone mentions

Night Gallery, unfailingly,

this is the episode that comes to mind. Embodying as it does every one of the

qualities/liabilities listed above as representative of the series as a whole, "The House" is perhaps the quintessential

Night Gallery episode. But in this instance, all

that evasive dialog and narrative ambiguity really pay off in an indelibly atmospheric story that perhaps makes not a lick of sense, but captures

precisely the strange, floating quality of dreams and the way they never quite

seem to hold together in the bright light of day.

I was

just 13 years old when this episode premiered in 1970, and trust me in this,

you cannot imagine how deeply this episode got under my skin. To use the vernacular of the time,

it was a mind-blower. It wasn't any one particular thing about the episode, but

rather all of its elements combined to make it a uniquely unsettling TV experience. I mean, what kid can make sense of eerie eroticism? "The House" episode is one I never forgot, and I revisited it every chance I could when it cropped up on reruns. (In those pre-DVD days, anticipation played a significant part in the cultivating of pop-culture obsessions. Once a particular show aired, one had to

content oneself with memory until the summer reruns came along.)

|

| The use of slow-motion photography, already an overused cliche in TV commercials and counterculture films of the day, feels oddly innovative and fresh in this episode's dream sequences |

Looking at the episode today, I still feel its fundamental appeal for me lies in its eerie mood and

atmosphere of ambiguity. Something I'll attribute to its director, but only with the evenhanded observation that I'm certain none of it would have worked quite as well with another actress in the role. In

all these years, I've never been able to put my finger on precisely what quality

Pettet brings to this story. But it's essential and remains, rather appropriately, confoundingly elusive.

|

|

Keep In Touch- We'll Think Of Something: 2nd Season: Air date Nov. 24, 1971

In

this nifty Night Gallery outing,

real-life couple Joanna Pettet and Alex Cord team up (for the first and only

time in their 21-year marriage) in this supernatural update of the old film

noir trope of the man who thinks he has all the answers, only to cross paths

with a woman who's rewritten the book.

Directed

and penned by

Gene R. Kearney,

screenwriter of one of my favorite underrated Diabolique-inspired

thrillers: Games (1967), "Keep

in Touch - We'll Think of Something" casts Cord as Erik Sutton, a musician who

concocts elaborate, ever-escalating schemes to meet his dream girl. That is to say, a woman he has only seen in his dreams…he really has no idea if

she is a real person or even exists. However, Sutton doesn't let the fact that

she may only be a figment of his imagination dissuade him from exhausting and

even harming himself in her pursuit.

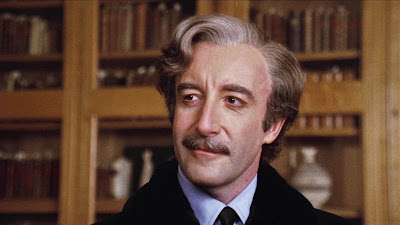

|

Mr. Groovy

Long, styled hair; sideburns; porn-stache; rugged features; and a form-fitting

wardrobe of leather and suede. Alex Cord threw my adolescent hormones into overdrive |

When he, at last, discovers the vision haunting his dreams is an actual, flesh-and-blood being

– an unhappily-married woman of mystery named Claire Foster – we realize in an

instant just why his search for her has been so fervent; for she comes in the exquisitely

beautiful, vaguely celestial form of Joanna Pettet.

But

if the visual compatibility of these two near-perfect physical specimens augers

a fated meeting of two kindred spirits, then a plot twist revealing Sutton's object of obsession may harbor an obsession or two of her own paints these dream lovers in a decidedly

darker palette.

"Keep

in Touch" successfully builds upon the enigmatic dream-girl persona Joanna Pettet

established so vividly in "The House." In fact, "Keep in Touch" feels in

many ways like an "answer" episode to "House," incorporating as it does a similar "dreams vs. reality" narrative with a Cherchez le Femme overlay which has Alex

Cord's character acting as the surrogate for every viewer left intrigued by

Pettet and that earlier segment's ambiguity.

As a supernatural

noir pair, Pettet and Cord make an outrageously sexy couple (in an über-hip, '70s way), their palpable chemistry placing one in the position of rooting for the

couple's hookup even while sensing there to be something a tad duplicitous in the mystery woman's suspiciously empathetic manner.

Best of all, in the tradition of some of the best film noirs, the ostensibly objectified

female turns out to be the more complex character and the one revealed to be holding

all the cards. Once again, Joanna Pettet acquits herself nicely in a made-to-order episode and easily steals

every scene with a persuasive performance and her unique star-quality presence.

The Girl With The Hungry Eyes - 3rd Season: Air date October 1, 1972

This episode is actually Joanna Pettet's

fourth and final appearance on Night

Gallery, but I've listed it here in the third position because it completes what I consider to be Pettet's Dream Girl Trilogy. A rather

exceptional episode titled "The Caterpillar" precedes this one, but it's the sole Night Gallery outing to cast Pettet

in a fundamentally traditional role. "The Caterpillar" casts her as a wife, a romantic ideal, and a lust object, all rolled into one. And though functional to the plot as a credible figure of desire for the male protagonist/villain, as written, her strictly ornamental character has no objectives to speak of, and does nothing to advance the plot herself.

"The Girl with the Hungry Eyes," on the

other hand, is an answer to an adolescent fanboy's prayers. Adapted from a 1949

short story by Fritz Leiber and directed by John Badham (Saturday Night Fever, Reflections of Murder) "Hungry Eyes" is another updated nourish tale featuring an icy femme fatale; this time out, a soul vampire who lures men to their doom out of

desire for her.

James Farentino plays David Faulkner, a

down-on-his-luck photographer whose fortunes change (but luck runs out) when a

nameless woman (Pettet, known simply as The Girl) wanders into his office wanting

to be a model. Although lacking in modeling experience or even a personal history, The

Girl proves a natural in front of the camera, skyrocketing Faulkner to fame as

the exclusive photographer of the woman who has become, practically overnight, the

hottest face in advertising.

|

Photographer to the stars Harry Langdon is credited with

all the photos attributed to James Farentino's character |

But for Faulkner, new-found success brings with it the nagging sense

that he has unwittingly entered into some kind of Faustian bargain. Fearing

that in exchange for riches, his photographs of The Girl - which seem to

inflame an obsessive, trancelike desire in men - have unleashed a kind of vampiric

scourge on the world, Faulkner seeks to unearth the mystery behind "the look" he's

convinced sends men to their doom.

|

John Astin, director of "The House" episode of Night Gallery,

appears as Brewery magnate Mr. Munsch |

Serving almost as meta-commentary on my own obsession

with Joanna Pettet's Night Gallery

career, "The Girl with the Hungry Eyes" builds a solid, very sexy supernatural

suspenser around that indefinable something we all seek in (and project onto) those

idealized creatures we deify in the name of fandom. And as a fitting vehicle for Pettet's

final Night Gallery trilogy appearance, "Hungry

Eyes" provides her with the opportunity to be the most forceful she's ever

been. Playing a woman who doesn't suffer fools gladly, there's a kind of bitch-goddess kick to Pettet's cool awareness of exactly what kind of effect her looks have on men. A kick made all the more exciting because of the feminist subtext inherent in having a woman turning the tables of the objectifying "male gaze" on men...to homicidal effect.

Pettet's character is fully in charge in this episode, and there's no small level of eroticism in the tug-of-war byplay she has with Farentino. With her husky voice, commanding presence, and penetrating gaze, Pettet comes across as more than a match for any man. Whether intentional or not, "The Girl with the Hungry Eyes" brings the Dream Girl Trilogy to a satisfying conclusion. The cumulative effect is a subtle and controversial point about the degree to which a woman owns herself and her appearance and to what extent men project their own fantasies upon them.

Not to be ignored (and certainly fitting with a male adolescent's point of view) is the equally persuasive notion that these episodes embody a kind of naif, fear-of-women trilogy. In these episodes, sex and feminine allure are intrinsically connected with danger and death.

However interpreted, what I now find I'm most grateful for is the way these episodes depicted women. They breathed fresh and provocative life into the feminine mystique, creating fascinating women of mystery during an era known for its "let it all hang out" transparency. In addition, they proved marvelous showcases for Joanna Pettet's versatility. They made the most of what I think is her one-of-a-kind ability to appear to inhabit the ethereal and corporeal worlds simultaneously.

The Caterpillar - 2nd Season: Air date March 1, 1972

My

strong affinity for the episodes which make up the unofficial Joanna Pettet

Dream Girl Trilogy is so firmly rooted in my adolescence and decades-long crush on Ms. Pettet; I concede that I speak of these episodes with nary a trace of objectivity. I have no idea how others respond to them; I only

know they represent my absolute favorite episodes of the entire series. That said, I'm comfortable recommending the episode "The Caterpillar" as one of Night Gallery's best. One so successfully creepy and well-done, you don't have to be Pettet-infatuated to enjoy it.

Directed by Jeannot Szwarc (helmer of the terrific TV movie, A Summer Without Boys), this episode is another Rod Serling teleplay, adapted and significantly retooled from a short

story by Oscar Cook titled Boomerang. A macabre Victorian-era love triangle set on a tobacco plantation in Borneo, "The

Caterpillar" is a revenge tale with a nasty twist. It's about a man (Laurence Harvey) who

devises a diabolical plan to win the beautiful wife (Pettet) of his elderly business

partner (Tom Helmore). A plan that (as it must in shows like this) goes nightmarishly wrong. Laurence Harvey and character actor Don Knight star in the episode and walk off with the lion's share of honors in this atmospheric piece which I recall

finding uncommonly creepy when I was young.

Joanna

Pettet is once again the object of obsessive affection, but her role is so

slight one is left to assume, overall quality of the script and production notwithstanding, that her longtime friendship with Laurence Harvey played a significant part in her accepting

it. (She would co-star with Harvey in his final film–which he also directed–the oddball cannibal horror feature Welcome

to Arrow Beach -1974.)

While

Pettet is photographed lovingly and offers a not-unpleasant change of pace as the

reserved, principled wife of a man old enough to be her father; for me, it just

feels like a waste of natural resources. She's beautiful, yes. And she does convey a certain mystery about her that makes you wonder just why a woman of such youth and refinement would be content in such an isolated environment, but I think Pettet brings this to the role; as written. I don't really think there's that much there.

Which brings up the issue of why these remarkable Night Gallery showcases failed to launch Pettet into the kind of stardom she deserved. Old Hollywood always seemed to know how to

showcase their glamour stars (did Hedy Lamarr or Marlene Dietrich ever play a

housewife?), not so much Hollywood in the '70s. In my opinion, Joanna Pettet wasn't particularly well-used by either television or films following her Night Gallery years. She remained a near-constant figure on episodic TV and Movies of

the Week in the 70s, but her roles were akin to casting a diamond to play a

Zircon. Appearing in projects that muted rather than emphasized her unique appeal,

she just always struck me as so much better than a lot of her latter-career material.

In 1967, Shirley MacLaine starred in an Italian anthology film titled Woman Times Seven. Because I consider these Night Gallery episodes to represent some of Joanna Pettet's best work, AND because this is a film blog, I've taken the liberty of visualizing Pettet's four TV excursions into the macabre as a single, four-episode anthology film; Woman Times Four, if you will. A tribute to one of my favorite underappreciated actresses of the '70s.

Unforgettable.

|

All Night Gallery paintings by Thomas J. Knight

|

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2016

.JPG)